Introduction to OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap is a collaboratively-edited worldwide geographic database. Its dataset is distributed free of charge under the Open Database License. The scope of the project has grown way beyond its original goal of providing a freely-available road atlas, and now covers a vast range of geographic features. In most parts of the world, the completeness and quality of the dataset is equal (and often superior) to paid commercial options, making OpenStreetMap an excellent resource for geospatial applications.

What are geographic features?

Broadly speaking, a geographic feature is any fixed object on the surface of the Earth (or underground), both natural and man-made. In computer applications, features are represented as points, lines and polygons. Determining their characteristics, and how they relate to one another, forms the basis of geospatial analysis.

The OpenStreetMap data model

The OSM data model consists of two principal elements: nodes and ways. A node represents a single point, identified by its latitude and longitude. A way is an ordered list of nodes, forming a polyline. A way that is closed (its start and end node are the same) can be used to form a simple polygon.

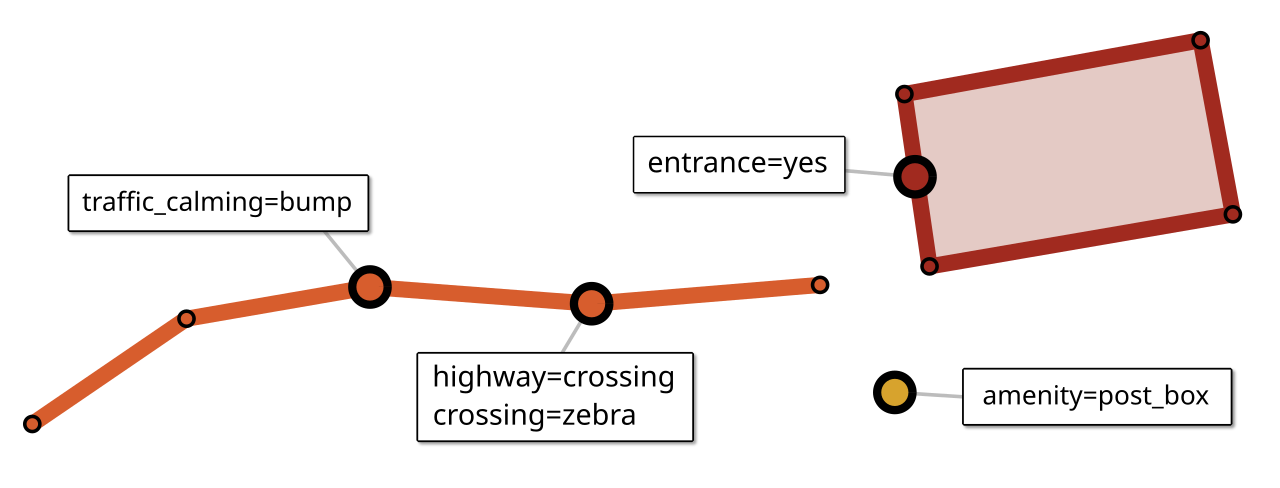

Nodes and ways can have one or more tags — key-value attributes that describe what kind of geographic feature an element represents (a street, a lake, a shop), as well as additional details (speed limit, depth, opening hours). This OSM page lists how various features are mapped.

The majority of nodes exist only to define the geometry of ways, but many nodes represent distinct features. These feature nodes can be part of ways — a speed bump along a road, or the entrance of a building — or can stand alone, marking features that are too small to be drawn as polygons: mailboxes, streetlamps, fire hydrants.

Generally, each element represents a single real-life object. Sometimes, a feature can be more than one “thing” — for example, a hotel (tagged tourism=hotel) that is also a restaurant (amenity=restaurant). Conversely, streets are often broken into separate ways, to reflect segments with different speed limits, parking rules or surface quality.

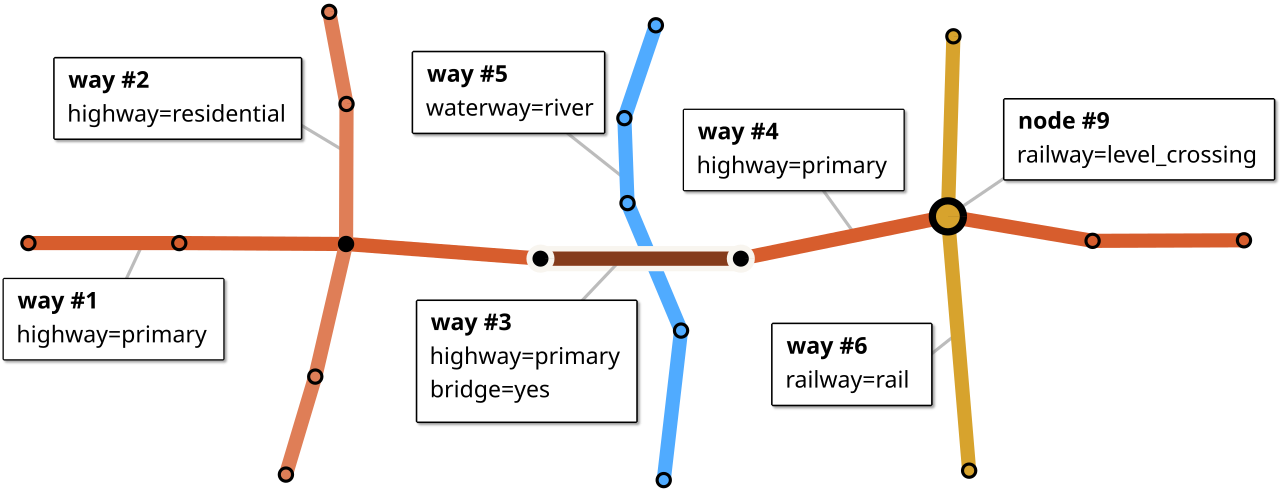

Features can be connected to each other through shared nodes. Two streets must have a common node to form an intersection. A road crossing a railway at the same level must have a shared node, as well. Railway crossings are always tagged (to make the mapper’s intent clear), for street intersections tags are optional (The presence of traffic lights is indicated with highway=traffic_signals).

Conversely, a bridge doesn’t share a node with the river it traverses. If two roads cross one another without a shared node, at least one of them must be a bridge or a tunnel.

Most ways can be drawn in either direction, but there are a few notable exceptions:

One-way streets should be drawn in the direction of traffic flow (although reverse flow can be indicated with

oneway=-1)Waterways must be mapped in flow direction.

Cliffs and retaining walls: The lower side of the terrain must be on the right.

Coastlines: land on the left, water on the right.

Relations

The OSM data model has a third kind of elements — relations — which combine multiple elements into more complex structures. A relation can contain any combination of nodes, ways, and other relations. Each member can have an optional role.

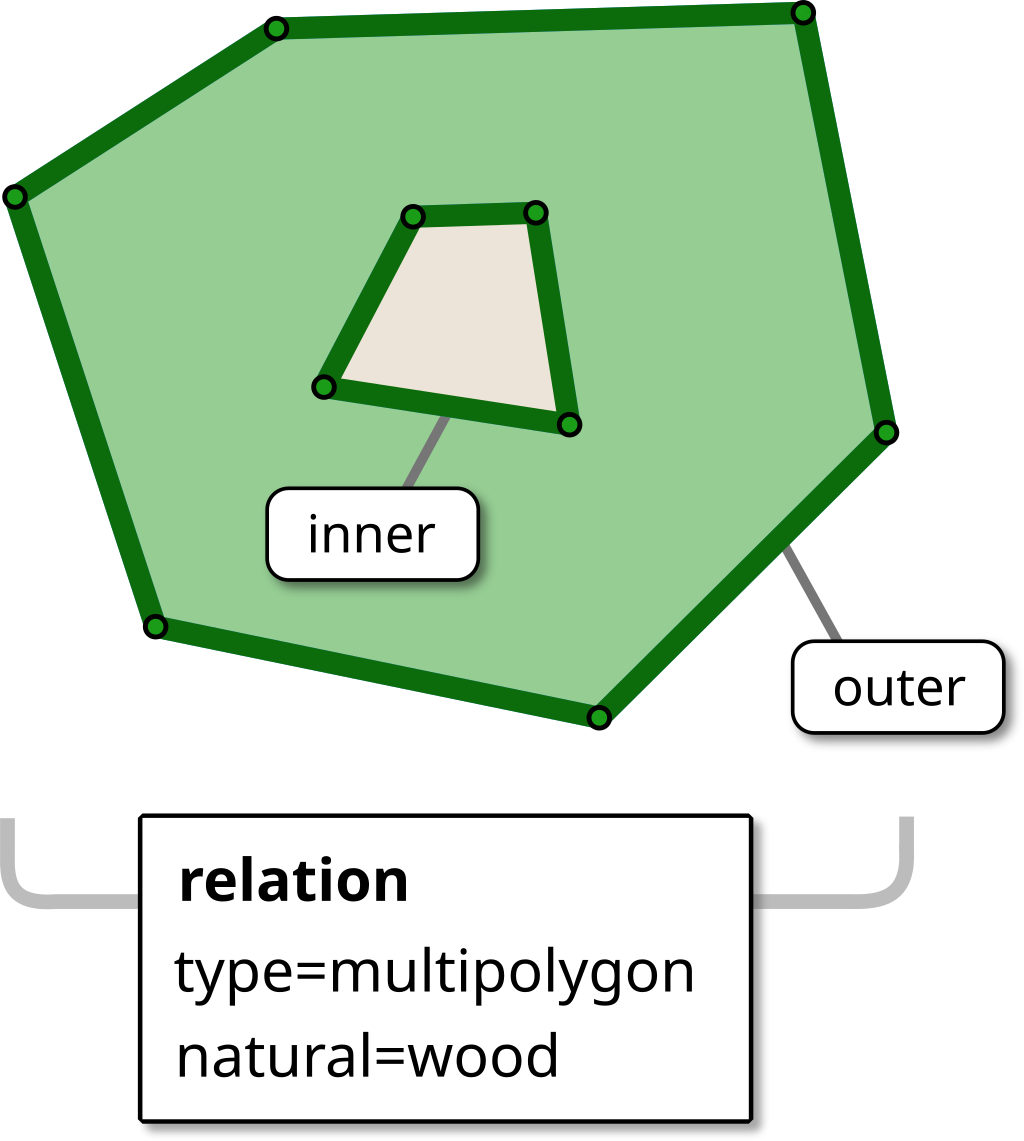

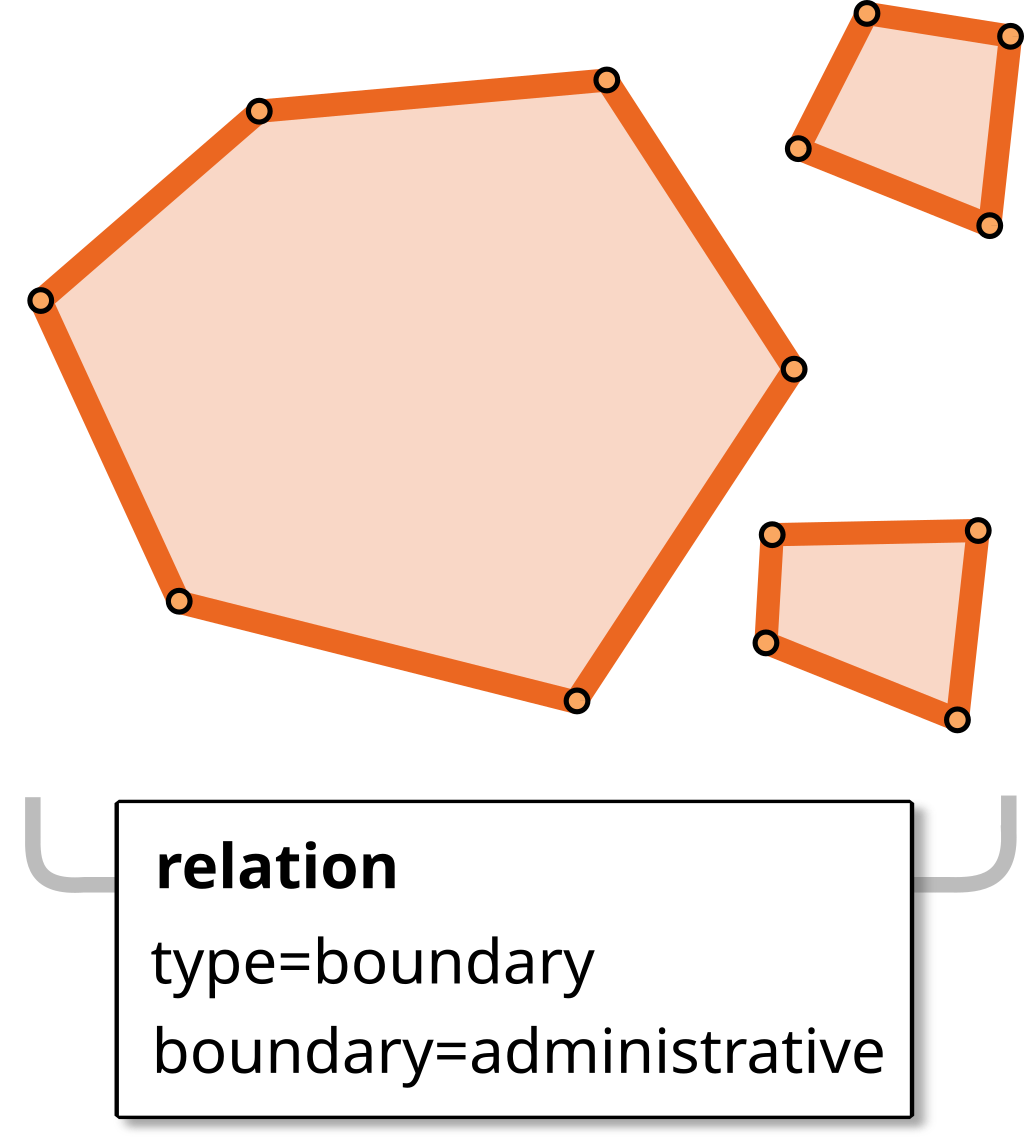

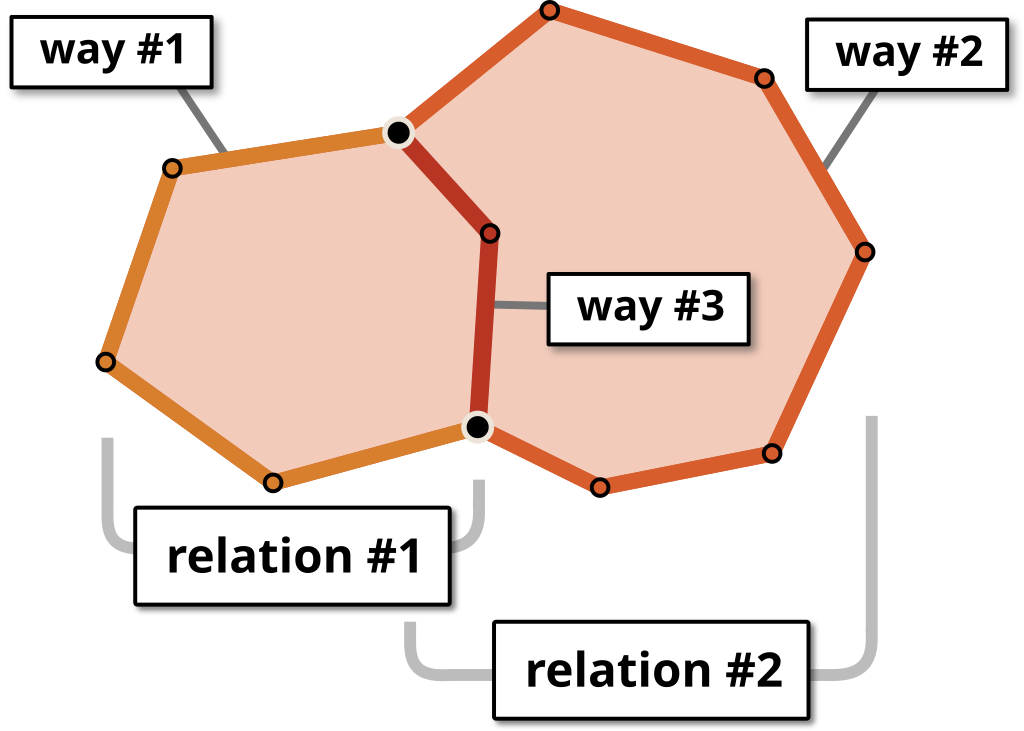

Relations are commonly used to represent non-trivial polygonal shapes: polygons with holes, or multi-polygons. Examples: a wooded area with a clearing in the center, or a country with exclaves.

Whether a way forms part of the shell or a hole is indicated by the outer or inner role. (This could be determined programmatically, but requiring the role of the rings to be explicit simplifies processing and makes it easier to spot mistakes.)

An element can be part of multiple relations, with a different role in each. For example, a way that forms part of an island’s shore would be an outer member of the island relation, and an inner member of the lake.

Relations are convenient for dividing the boundary of a large polygon into individual ways, or sharing ways among multiple geometries. Imagine two adjacent counties: Someone wanting to edit the common border only needs to edit the nodes of the shared way.

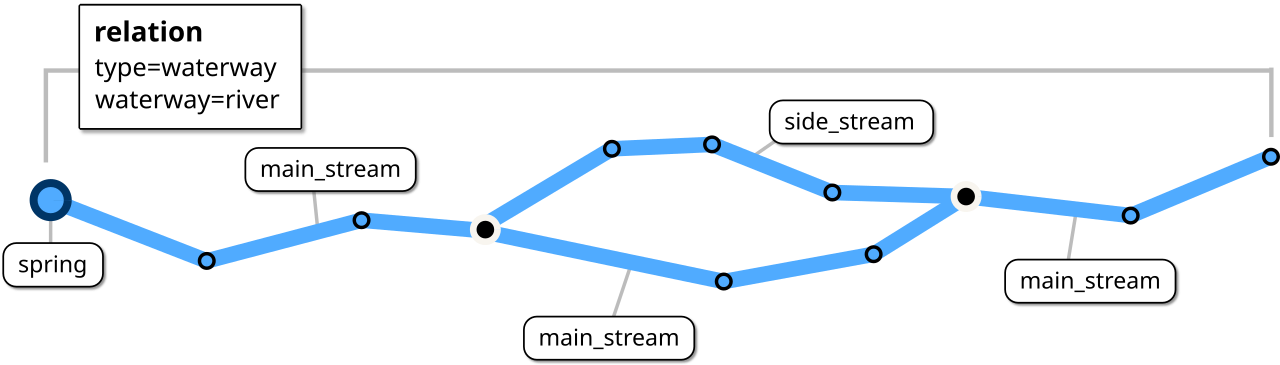

Relations are also used to build complex non-polygonal structures, such as a river that splits into multiple branches. Here’s an example of a river composed of multiple ways — the roles main_stream and side_stream may be useful for applications dealing with boat navigation, or help map-renderers decide which details to omit at lower zoom levels.

Stricly speaking, the spring member isn’t needed, but by explicitly including it, data consumers can quickly determine the river’s origin, without having to analyze its geometry.

How to obtain OSM data

Every week, the OpenStreetMap project publishes a complete copy of its worldwide dataset. This planet file is encoded in a tightly-compressed format based on Google’s Protocol Buffers (file extension .osm.pbf).

There are also multiple services that provide smaller extracts, both for various countries and regions, as well as custom areas.

The full planet is also available for download as a pre-built GOL (GeoDesk’s native file format) on OpenPlanetData.com (updated daily).

So, what do you do with all this data? This is where GeoDesk comes in!